By Sunil John

In 2008, when we launched the first edition of the annual ASDA’A BCW Arab Youth Survey, two themes dominated the discussion from Dubai to Davos: The Middle East’s ‘youth bulge’ and its ‘untapped youth dividend’.

Fifteen years later, and despite the Arab world population becoming younger, realising this so-called ‘youth dividend’ still appears a distant prospect.

Youth unemployment in the Middle East & North Africa has worsened, and at 26 per cent, is higher than the world average by around 13 per cent.

According to the World Bank, one in three young people (32 per cent) aged 15 to 24 are neither employed nor in education or training, and the United Nations reports that the region must create some 33.3 million jobs by 2030 to absorb the vast number of young people entering the workforce.

Without question, this is a daunting task for governments. The challenge is further exacerbated by the declining confidence of Arab youth – particularly those in North Africa and the Levant countries – in the ability of their lawmakers to solve their most pressing concerns, notably, unemployment and rising living costs.

However, the old order is starting to change. Instead of looking to others for support in an increasingly uncertain world, today’s generation of Arab youth are learning to rely on themselves. And while this is, in many ways, evidence of the failure of regional governments to provide a secure future for the next generation, it is also a heartening sign of the determination of Arab youth to chart their own course.

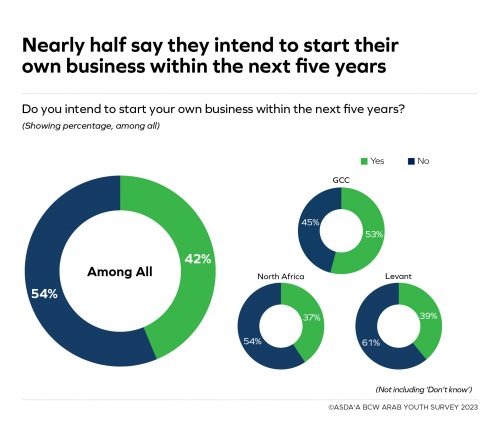

According to the findings of the 15th ASDA’A BCW Arab Youth Survey, nearly half of young Arab men and women across the region plan to start their own business in the next five years. GCC youth appear to have the most entrepreneurial drive (53 per cent), followed by their peers in Levant (39 per cent) and North Africa (37 per cent).

This is unsurprising, considering the sums GCC governments have invested in startups and incubator initiatives, from Hub 71 in Abu Dhabi to the US$100 million Venture Capital Fund for Startups announced by Dubai. In Saudi Arabia, the number of small businesses, many of them women- and youth-led, has more than doubled to 1 million, since the launch of the Saudi Vision 2030 programme in 2016.

Outside the GCC, the will to start a business may be there, but the way is still unclear for many. About three-quarters of Arab youth in North Africa (73%) and Levant (79%) say it is difficult for young people in their country to start a business, compared with 42 per cent of GCC youth who say so.

Young entrepreneurs require a hand up rather than a handout to make their way in the world – specifically, less red tape, more vocational training, and more affordable (and accessible) finance. Our research also found that Arab youth most want to start their business in technology, e-commerce, and the creative industry.

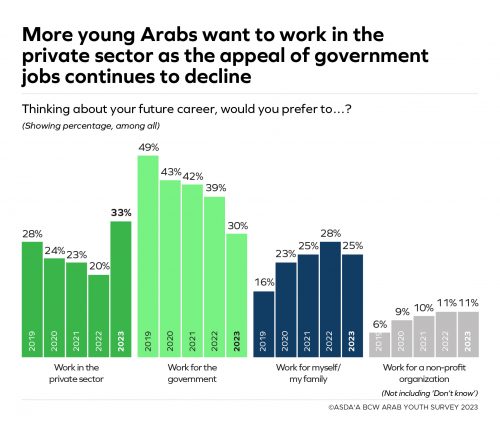

Running alongside this rising trend in entrepreneurialism is the increasing desire of Arab youth to pursue a career in the private sector rather than government. While nearly half of the participants in our 2019 study said they would rather work in the public sector, less than a third (30 per cent) in this year’s survey say they prefer a government job. A full 33 per cent of Arab youth want a business career instead, a 13 per cent jump since 2022.

These findings are a call to action for both government and the private sector. Governments must introduce the necessary regulatory frameworks and invest in the infrastructure required for Arab youth’s entrepreneurial ambitions to thrive. Businesses must provide better access to the workplace for young school-leavers and college graduates, and the right career development pathways for the region’s rapidly evolving Arab national workforce.

Arab youth are increasingly ready to go it alone, and for this, they deserve support as well as praise. Governments and businesses must play their part to ensure their potential is fulfilled.

ENDS

Published in Entrepreneur Middle East. Read it here.